Worthington Assembly Reveals What It Takes To Buy Parts

This is a guest post by Chris Denney, CTO of Worthington Assembly.

Octopart makes things so easy. Using Octopart's excellent BOM Tool, you know exactly what your BOM is going to cost you, and if you add in your PCB costs and your assembly costs, you've got your bottom line, right? Oh, how sweet it would be. Manufacturing is just not that simple. Then again, if you're just buying a PCB or two from OSHPark and hand assembling them yourself, then yeah, it's that simple. But if you're working with a contract manufacturer (CM), there's a lot more to consider when buying parts.

Markup

What an ugly word, "Markup". It makes you think of fat cat executives in leather chairs, chomping a big Cuban cigar, glass of Scotch in one hand, hundred dollar bills in the other, laughing maniacally at the money he makes off of the poor chumps that don't know about markup costs. But the real picture is honestly much different.So what exactly is markup and why is it necessary? Basically, markup is a percentage fee that a CM will charge you for buying parts. Not all CMs charge the same amounts. We've heard crazy numbers like 50%, but that's probably when the government is involved and the CM knows he'll have mountains of red tape, stop and starts, and insanely late payments to deal with. But generally speaking, you should expect a CM to charge about 25% or less on your BOM for buying material. The next logical question to ask is "Why so much?" It comes down to a few things.

- Cash

- Purchasing

- Management

- Receiving

Cash

This is the easiest to understand. Money isn't free. If a CM has to go out and buy $10,000 worth of material, they've got to find that money from somewhere. If they have it on hand, they'd like to make money from it, just like you would if you had $10,000 sitting around. You'd probably invest it in a mutual fund, or at the very least, lock it up in a CD. So the CM has to justify getting that cash, either from their own reserves, or from a bank loan. Either way, always remember that cash isn't free.Purchasing

Somebody has to actually order all of this stuff. It's fantastic when you can buy everything from one distributor and that distributor has the best pricing on all of the parts. But that happens about once in every, oh say, 50 jobs or so. In reality, it's pretty rare that any one distributor even carries all of the parts for one job, let alone have all of those parts in stock, and then have the best pricing on all of the parts.So you have to shop. And you can't just hire anybody to go shopping. The people you hire to buy all of these parts better be sharp because they're going to be spending a lot of money. Probably millions of dollars per year. And you want to make sure they're not making mistakes, because even minor mistakes can be very costly. So you hire good people for this work, and good people are not cheap.

Management

Ok, so all of the parts are on order. Now, when do they all arrive? It may not be very straight forward. Some might come from Minnesota, some from Texas, some from China. Either way, you can’t expect them all to arrive at the same time, or even ON time. Minnesota gets snow. Texas gets hurricanes. China gets… well China gets a lot but Chinese New Year is the real pain in the neck. And if you’re a CM who’s promised a certain delivery date, you need to make sure you’ve got your stuff together and you’ve coordinated all of this to make sure the parts arrive early enough so that you still have at least a few days to build everything.Whenever customers want to supply us parts, this is one of the biggest hassles we run into. Many of our customers just aren’t accustomed to managing a supply chain (some are, and they’re great at it, but not many). It’s not uncommon for parts to show up either late, or short the total number needed. Managing all of this is not easy, so the CM must account for this process.

Receiving

So now all the parts have arrived and they’re sitting in pretty brown boxes on a cart just waiting for somebody to do something with them. This is where the fun begins. All those boxes need to be opened, all the paperwork needs to be checked to make sure what was ordered was actually shipped, and then each bag, reel, tube, box, etc. needs to be checked to make sure it matches the order EXACTLY. Not 1 number different. You’d probably be shocked at how often distributors send the wrong parts. It’s at least a bi-weekly occurrence here. The really fun ones are when the bag is labeled with the correct part number, but the parts inside are wrong. Or the bag says we should have 60 but they only send 50 (Why do the numerals 5 and 6 have to look so similar? Hmm!? So frustrating.)And that’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to receiving parts. Are any of them damaged, loose, exposed to moisture, etc. The list goes on. A good CM will shield you from all of this and can make sure you get a quality product on time without having to deal with all of these headaches.

A side note here, if you choose part numbers from the Octopart Common Parts Library (CPL), you'll save yourself some money. As the CPL becomes more and more popular, the price of these products will continue to come down, and CMs will likely be buying these parts in higher volumes and saving on the price per piece. If the CM already has the part in stock then they don't have to receive it either. There's a lot of advantages to choosing common parts. Ultimately it will save you money and help smooth out potential manufacturing issues too.

Pro Tip: If you want to save some money, you can "pay yourself" the markup fee, by buying your own parts and shipping them to your CM. Most CMs are perfectly fine with this, but they'll want you to consider their needs before allowing you to do this. And the primary needs are packaging and excess.

Packaging

A CM cannot accept material in just any old package. Except for thru-hole components, loose parts are almost never acceptable. This is because a CM is going to use a machine to pick and place all of the parts automatically. Imaging trying to present this pile of switches to an automated machine? It would be a nightmare.Another fun one is when parts come in damaged. Pick and place machines do NOT appreciate damaged leads. They use the leads to identify the part on the nozzle before placing it. If the leads are damaged, it will never place it, so an operator will need to use a set of tweezers and a high power microscope to bend these back and enable the machine to place them.

But my absolute favorite, is this one. Components in tape, but the tape is not continuous. It’s all cut up. At this point, you basically either place these parts by hand or you “mickey mouse” them into the machine somehow to allow the machine to place them. Either way, it’s almost always expensive and a pain in the neck to handle.

The long and short of it is you want all parts to come in continuous tape (having tape cut from a larger reel is fine, you just want it to be continuous), tubes, or a tray. Any of those 3 packaging methods are what a CM is going to need in order to automate the assembly of your product.

Trays work perfectly fine. They're very common for expensive components.

Accounting for Wastage

Your CM is going to waste some parts. On a 1 piece run, a 20 piece run, or a 2,000 piece run, some parts will get wasted. They won't necessarily lose the parts (they might lose some discretes but IC's and other large components rarely get lost) but they'll waste them.Whenever a feeder is loaded, some section of the tape will get exposed and the parts will advance beyond the point where the machine can pick from them. If you look at tape you'll notice the sprocket holes on the left hand side of the tape. This is where the machine pulls the tape through the feeder to advance the tape and expose the next component to the vacuum nozzle. These sprocket holes need to line up with the sprocket wheel itself so that it can advance. Generally that means you'll lose the first 3 components on any piece of tape.

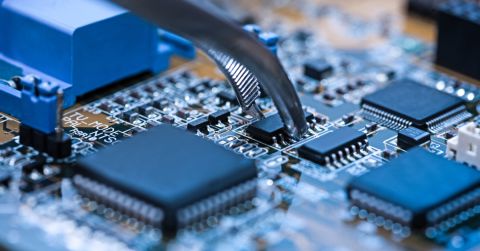

A typical 8mm feeder. This one is manufactured by MyData

The feeder has a channel for the tape to slide through and a plow for "plowing over" the cover tape that holds the components in place.

The dull looking aluminum is the plow and if you look very closely you can make out the far side of the cover tape being peeled off.

There's a pickup point in the feeder where the machine needs to be able to fit the vacuum nozzle and pickup the exposed component. Here you can see the pickup point.

Notice the open channel below the pickup point. This is where the sprocket holes will be, and the sprocket of the magazine that this feeder gets loaded into will fit inside the sprocket holes and advance the tape. But the first sprocket hole that the magazine can reach is past the pickup point. This is so that the machine can pick every single component of the tape, all the way to the end of the tape. Yes, it may waste a couple of components in the beginning, but it picks every last component to the end of the tape. This way, if some of the pockets at the beginning of the tape are empty, you probably will be able to pick every single component from this tape. But in general, that's pretty rare at lower volumes. You will end up having plenty of cut-tape, where you will waste the first 3 components. If you look at the image below you will notice three 0603 resistors that are exposed. These 3 resistors will not get picked up by the machine because the machine will need to begin advancing the tape from this point, and no sooner. So say goodbye to those first 3 parts.

After that, it's a bit of crap shoot as to how many components you will lose. Pick and place machines are high speed, enormously complex machines. You're placing components anywhere from 5,000 to 30,000 components per hour. Some machines, even more. It's not uncommon for a machine to mispick a component or misplace a component for no obvious reason. At those speeds it's bound to happen. Just look at this thing run.

So we generally buy about 5 to 10% extra material based on a few different factors.

Discrete components are generally very cheap. If you need 20 resistors, we'll probably just buy 200 or more, because the price will be just about the same for 200 as it would be for 20. And the extra tape allows the operator to handle the components easier, than a tiny little strip of 20 resistors.

The more expensive IC's, say a dollar or more, we'll generally buy about 5 extra, depending on how many we're building. If we're building thousands, we may buy 20 extra. If we're only building 100, then 5 extra is plenty. You're bound to lose or damage some, even at only 100 pieces. So having a few extra will ensure that we deliver all of your boards on time.

For very tiny diodes, or SOT-23 style components, we may buy an extra 10% or so. This is because those tiny parts can be easy to drop and lose on a manufacturing floor. And the components have such tiny features that the machines will occasionally mis-recognize a couple of them and reject them, at least at the beginning until things start humming along nicely.

For larger parts, or very expensive parts, we may end up buying exact count or maybe just 1 extra. If the part is less than $10 but more than a couple bucks, we'd probably just buy 1 extra. But if you have an MCU that costs $100 or more, then exact count is fine and we just manage that ahead of time so that everybody is aware that we cannot lose a single one.

Here's another pro tip. Do your best to use the Octopart Common Parts Library when choosing specific Manufacturer's Part Numbers. If you specified some strange MicroUSB port that your CM has never seen before, and then they run out of that part or lose some parts, or are shorted a part, there will be inevitable delays. But if you chose a MicroUSB port from the Common Parts Library, then your CM will likely have extra of that in their own stock and be able to pull from that, saving everybody a lot of time.