PCB Layout Constraints That Help Manage Component Obsolescence

Just about everyone in the world of engineering has heard some variation of the “Iron Triangle” theory. It’s a popular way to talk about what is or isn’t possible among those given the task of getting things done. Basically, it is a philosophy that says you can get something done fast, cheap, or good; pick two. For example, when designing a PCB for an aircraft, cheap goes out the window, fast takes a back seat and quality is paramount. Alternately, when designing a PCB for next season’s flashy throwaway toy, quality is the lowest concern, fast is a must, and it better be cheap. Once a circuit design is basically finalized, finding the best way to use the allotted space for a layout requires making many decisions about tradeoffs. These will have a large effect on the quality of the product throughout its lifetime. What follows are some suggestions regarding these important considerations.

Plan on Extra Time for Routing Tight Spaces

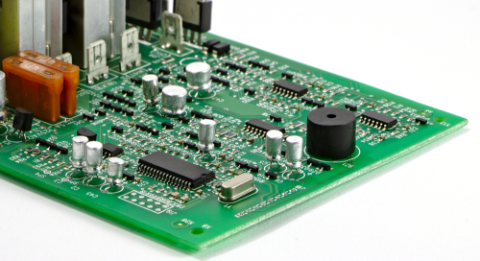

Since there is no iron shoe-horn for cramming dozens of inexpensive features into a tiny space, tradeoffs quickly become necessary. In many products, the outline of the board is predetermined by mechanical properties of the larger assembly, and the location of the larger components are restricted by their heights. These layouts will usually take much longer because of a lack of component placement flexibility and the need to comply with numerous design requirements. Redesigning a circuit using more expensive specialized components in order to reduce the required footprint is sometimes a necessary tradeoff when all else fails.

Devices that use high voltages have the constraint of needing to maintain a substantial isolation voltage between signals or mechanical assembly features. Spending additional time on placement and routing should be expected with these designs as well. Tradeoff decisions, if they are considered, will also address quality and expense usually within the circuit design itself.

Small spaces require careful planning.

Time is Money vs. Money is Money

Board designs that end up mounted inside of large pieces of equipment are not usually constrained by the amount of space available. In these situations, there are a lot of tradeoffs that can drive the size of the PCB’s outer dimensions. Many designers will try to reduce the cost of the bare board by prioritizing a smaller board size when doing part placement. This is understandable, since it’s logical to not want to pay for things that you don’t need. That said, it can be a counterproductive use of a designer’s time if they fixate too much on space saving parts placement when it isn’t a necessity. The temptation to cram everything together can lead to problems and lost opportunities down the road, and the repercussions are not obvious at the time.

Pay attention to cost vs. benefit with respect to time spent adjusting your layout.

Part Placement Form and Function

When working on circuit boards that will be manufactured in low quantity but have a high probability of requiring intensive troubleshooting, it is good practice to prioritize arranging components in a geometric fashion that reflects the functionality of the circuit than trying to save space. These tend to be boards used in experimental machinery or custom manufacturing equipment. This practice helps with troubleshooting since the function of each part is more obvious. Keeping similar blocks of circuitry arranged in a duplicated fashion will probably use more board real estate, but you won’t waste time figuring out which field effect transistor does what from one section to the next. Here, the small expense of more board space can be a trade-off for a big headache.

In general, when you’re grouping the initial blocks of components, if possible, it’s a good idea to try to leave multiple paths to route each signal. That may mean backing off a pull-up resistor a tad or moving the decoupling cap to the bottom layer, but it will make your life easier in the long run. Of course, there are exceptions, such as oscillator circuits and high speed data components, whose distance from part to part has to be minimized because of noise considerations. However, backing off a bit where you can will help you avoid getting boxed in during the routing process. That may sound like simple common sense, but it’s easy to overlook in the early stages of part placement.

Planning for the Next Revision

It is a good practice to ensure that your PCB’s layout is flexible for redesign, especially if your design is meant intended to have a long lifecycle. Sooner or later, every PCB in a continuing product line will require a redesign as a result of part obsolescence. Having to move unrelated components so that you can replace an obsolete part adds risk to a design change. Even for new designs it is possible to choose a part that is obsolete to begin with when relying on a standard parts library. Checking parts using Online Search is a good way to ensure that this doesn’t happen. Altium’s BOM management tools have advanced parts selection and the BOM tool integrates seamlessly with Altium’s software. Using it is a great way to increase your productivity and improve quality for all of your board designs.

As discussed above, specialized parts can be necessary in a design, but they have a higher likelihood of becoming obsolete. Being cognizant of this when doing your layout can help your placement orientations accommodate the need to change the route of a signal in the future, even when parts are close together. Historical lifecycle data helps you to determine in advance which areas of a circuit might be better suited for a specialized part and which areas of the circuit should stick with standard parts. The tradeoff of taking a small amount of time upfront to use these convenient tools can save a lot of time, money and extra work down the road.

Have a question about part obsolescence? Contact an expert at Altium.