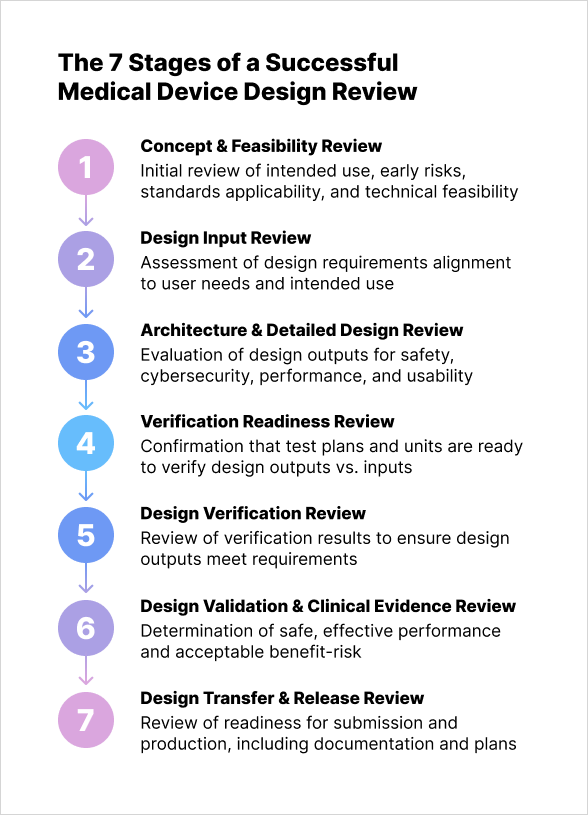

The 7 Stages of a Successful Medical Device Design Review

Design reviews are the guardrails that keep medical device development safe, compliant, and on schedule. For medical electronics in particular where hardware, embedded firmware, software, and human factors converge, reviews must do more than check boxes. Design reviews demonstrate traceability from user needs to design outputs, show that risks are controlled, and prove that safety and essential performance will hold up in the real world.

The U.S. quality regulation requires formal, documented reviews at appropriate stages of design. ISO 13485 mirrors these controls and recognized standards (IEC 60601-1, IEC 60601-1-2, IEC 62304, IEC 62366-1, ISO 14971) set the bar for what "good" looks like when electronics and software meet clinical practice.

This article maps a complete, seven-stage design review system that fits both FDA 21 CFR 820.30/QMSR and ISO 13485 Clause 7.3 and is tuned for medical electronics. For each stage you’ll find the inputs, the review process, and the expected outputs plus what’s uniquely important for medical electronic designs, from EMC and essential performance to software safety classification, usability, and cybersecurity (including SBOM expectations in FDA’s latest guidance).

Key Takeaways

- Medical device design reviews must demonstrate full traceability, from user needs to requirements, design outputs, verification, validation, and risk controls to satisfy regulations and ensure safe, compliant products.

- Each review stage serves a distinct regulatory and engineering purpose, ensuring risks, software lifecycle controls, usability, and electro‑safety/EMC are addressed at the right time.

- Medical electronics require early and continuous focus on essential performance, EMC robustness, and cybersecurity, including SBOM expectations, secure updates, and real-world electromagnetic environments.

- A structured seven‑stage review system becomes a living backbone of quality, enabling predictable development, defensible evidence for submissions, and resilient designs that perform safely in clinical and home‑use conditions.

Stage 1: Concept & Feasibility Review

What this stage answers first: Do we have a medically sound problem statement, a clear intended use, and early evidence that the concept can be engineered safely and remain compliant?

Inputs:

- There must be an initial use specification.

- Preliminary user and patient needs are considered.

- High-level hazard brainstorming is performed.

- Intended use environments (professional facility, home, special) are defined.

- Early technology options are explored.

Process: There needs to be a mapping between specification, relevant regulations, and standards so that a review can test whether the intended purpose and claims are realistic and whether early risks are identifiable and tractable.

This review confirms the team can plan the design, define inter-group interfaces (per 21 CFR 820.30(b) and ISO 13485), and integrate ISO 14971 risk management from the start, planning the risk management file. For electrical devices, reviewers identify applicable IEC 60601 standards (base, collateral like IEC 60601-1-2 EMC, and particular) to determine architecture and testing depth. For software/firmware, reviewers establish IEC 62304 classification and required documentation/verification rigor. Human-factors scope is clarified per IEC 62366-1 to systematically manage foreseeable misuse and user interface risks.

Outputs: The meeting produces an approved Design & Development Plan, a preliminary risk management plan, a standards applicability matrix, and a concept-level system architecture. It also records a go/no-go decision, documented minutes, and action items. These artifacts flow into the Design and Development File (ISO 13485)/Design History File (legacy QSR wording) and satisfy the "formal, documented review" expectation in 21 CFR 820.30(e).

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: Early EMC and essential performance thinking prevents later re-designs. Concept reviewers confirm that essential performance functions (those whose loss would create unacceptable risk) are identified and that the architecture can protect them under EMC stress, power dips, ESD, and single-fault conditions per IEC 60601-1 and IEC 60601-1-2. If wireless or radio coexistence is expected, the team charts the test strategy and the regulatory path now, noting FDA’s EMC guidance on gaps not fully covered by 60601-1-2 and the need to address common electromagnetic emitters.

Stage 2: Design Input Review

What this stage answers first: Are the design requirements complete, testable, and unambiguous, and do they reflect user and patient needs, clinical claims, and risk controls?

Inputs:

- Detailed design inputs covering functional, performance, interface, usability, safety, cybersecurity, and regulatory requirements.

- Inputs must address intended use and user/patient needs and include mechanisms to resolve incomplete or conflicting requirements.

- Risk controls from ISO 14971 analyses and usability risk controls from IEC 62366-1 feed into the inputs.

- Likewise, software safety class and life-cycle tasks per IEC 62304 are reflected as verifiable requirements.

Process: Reviewers verify that acceptance criteria allow conformance evaluation (21 CFR 820.30(d)) and confirm traceability between user needs/hazards and requirements. For electronics, they check environmental limits, power budget/derating, creepage/clearance, alarm logic, and essential-performance thresholds trace to risks and standards. Home-use devices must consider IEC 60601-1-11. Cybersecurity inputs cover SPDF expectations, threat modeling, SBOMs, and vulnerability management, aligning with FDA premarket guidance and Section 524B "cyber device" obligations.

Outputs: An approved Design Input Specification with full traceability to user needs, risks, standards, and regulatory claims. The minutes log any open items with owners and due dates. This review locks baselines that will drive design outputs, verification, and validation.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: EMC performance and immunity levels become explicit, including ESD, radiated/conducted immunity, voltage dips, and proximity RF sources per IEC 60601-1-2 Ed. 4.1. Power-supply quality, battery modes, shielding, and filtering are specified so that the eventual test plan is realistic. Inputs also codify logging, time synchronization, and secure boot for firmware, and the SBOM content/format expected for submissions and operator documentation.

Stage 3: Architecture & Detailed Design Review

What this stage answers first: Does the proposed architecture meet the inputs with defensible safety, cybersecurity, and usability by design and can it be verified?

Inputs:

- System block diagrams, schematics, PCB layout, power and thermal budgets, component selections, safety analyses, software architecture, partitioning and interfaces, state diagrams, and preliminary test methods.

- Risk analyses are updated with architecture-specific hazards and fault trees.

- The usability engineering file links early prototypes to use-related hazard mitigations.

- Software safety classification is confirmed (Class A, B, C) with 62304-aligned plans.

Process: The design review ensures outputs meet inputs, referencing acceptance criteria per 21 CFR 820.30(d). For electronics, the team checks IEC 60601-1 Ed. 3.2 compliance on insulation, creepage/clearance, leakage currents, protective earth, applied-parts classification, isolation, thermal design, and single-fault tolerance. EMC strategy is scrutinized against 60601-1-2 Ed. 4.1, covering shielding, grounding, and immunity risk. Software architecture is assessed for modularity, defense, secure updates, SPDF alignment, threat models, data flows, and FDA-consistent SBOM generation. Human-factors outputs (user interface, alarms, labeling, instructions) are reviewed against IEC 62366-1.

Outputs: Approved architecture/design outputs, an updated traceability matrix linking inputs to design elements, a refined V&V strategy, and a consolidated set of actions. The record shows that essential performance and basic safety have been engineered into the design and that verification is feasible.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: Reviewers verify that essential-performance paths are physically and logically protected: watchdogs, safe-state behaviours, redundant sensing where needed, and EMC-robust routing. They ensure that firmware update mechanisms are authenticated, that cryptographic keys are protected, and that the design anticipates post-market vulnerability handling now a formal expectation for “cyber devices.”

Stage 4: Verification Readiness Review

What this stage answers first: Are verification plans, methods, fixtures, and sample builds sufficient to prove that outputs meet inputs under the applicable standards and worst-case conditions?

Inputs:

- Complete verification plans and procedures

- EMC test plans that map to IEC 60601-1-2 Annexes with device-specific rationales

- Electrical safety plans for IEC 60601-1

- Software verification protocols tied to IEC 62304 tasks and software risk controls

- Usability formative/summative evaluation plans against IEC 62366-1

- Risk management verification steps from ISO 14971

- Cyber test plans (include secure boot, authentication, update, logging, and vulnerability scanning, with SBOM validation)

Process: The review checks test coverage, sample size, acceptance criteria, and traceability to inputs and risks. For EMC, reviewers confirm test levels, modes, and pass/fail criteria align with essential performance and safety for each use environment, noting FDA guidance may require tests beyond 60601-1-2 for real-world emitters. Software reviews verify unit/integration/system verification addresses safety classification and that defect management and configuration control meet 62304. Human factors review ensures summative usability testing evaluates critical tasks and use-error risks in realistic environments.

Outputs: An approved verification master plan and protocols, with clear entry/exit criteria and a build plan for test units and golden samples. The outcome documents readiness to execute verification without re-planning, supporting the “adequate evaluation of conformance” requirement in FDA’s design control rule.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: EMC pre-compliance scans and iterative board-level fixes save months later. The plan should stage pre-compliance early and reserve time for iterative mitigation. If radios are present, coexistence testing is scheduled. Power-quality and battery aging tests are aligned to expected clinical duty cycles. Firmware/FPGA bitstreams are reproducible and signed, with test logs saved for traceability and for eventual regulatory and customer cybersecurity transparency.

Stage 5: Design Verification Review (results)

What this stage answers first: Do verification results prove that design outputs meet design inputs across the full requirement set and applicable standards?

Inputs:

- Executed test protocols and raw data

- EMC and safety lab reports

- Software verification evidence

- Human-factors formative and summative reports where they close risk controls

- Metrology and calibration records

- Updated risk analyses with verification results embedded

Process. The review scrutinizes objective evidence, analyzing failures and deviations to plan corrective actions and linked re-tests. Risk files are updated for new hazards or residual-risk changes found during verification. Specific checks include EMC performance during immunity tests, electrical safety reports (single-fault, leakage, dielectric strength, lab accreditation), software traceability (requirements to test cases/results per 62304), and usability (critical use error elimination/control).

Outputs. A verified requirements matrix with pass/fail dispositions, an updated risk management file showing risk control effectiveness, and a consolidated list of corrective actions. The minutes record the decision to proceed to validation or to loop back for design corrections.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics. Essential performance behaviour under EMC stress is the non-negotiable success criterion; reviewers ensure no mode masking hides unsafe behaviour. Firmware and FPGA change control is tightened post-verification: any late change triggers impact analysis across EMC, safety, and cybersecurity. Where cybersecurity verification found gaps, the team aligns remediation to FDA’s SPDF philosophy and confirms SBOM completeness against the actual shipped software.

Stage 6: Design Validation & Clinical Evidence Review

What this stage answers first: In the hands of intended users, in the intended environments, does the device perform as claimed and deliver clinical benefits that justify residual risk?

Inputs:

- Summative usability test results under IEC 62366-1

- Design validation protocols and data

- Simulated-use or clinical study evidence as needed

- Labelling and IFU verification

- Benefit-risk analyses

- Clinical evaluation documentation per EU MDR Article 61 and Annex XIV, including a Clinical Evaluation Plan and Report and, where applicable, Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) plans

- For U.S. submissions, applicable clinical or simulated-use evidence aligned to indications

Process: The review confirms validation aligns with user needs and intended uses (FDA design controls) and that clinical claims are substantiated and consistent with labeling. It ensures usability testing covers all critical tasks and residual use-related risks are acceptable. For networked or update-dependent devices, cybersecurity labeling and operator guidance (including SBOM info, patching, and end-of-support) are validated per FDA guidance. For CE marking, reviewers verify the clinical evaluation meets MDR requirements for state-of-the-art, benefit-risk, and PMCF.

Outputs: A validation report demonstrating that the device meets user needs in its intended environment, finalized labelling and IFU, clinical evaluation conclusions and PMCF plan (if EU), and an updated overall residual-risk acceptability statement in the risk management report.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: Validation environments reflect electromagnetic realities: proximity to mobile phones, Wi-Fi, RFID, nurse-call systems, and consumer electronics in home care. Usability validation includes alarm handling and display interpretation under stress. Cybersecurity validation confirms that secure configurations and update procedures are understandable and feasible for clinical engineering teams, with clear instructions as FDA recommends.

Stage 7: Design Transfer & Release Review

What this stage answers first: Are we ready to transfer the design into production and submit/market the device with full evidence, controls, and lifecycle plans?

Inputs:

- The completed Design and Development File (or DHF under legacy terminology)

- Manufacturing procedures, including supplier controls

- Device master records and final risk file

- Post-market surveillance plan

- Cybersecurity maintenance plan (including vulnerability monitoring, coordinated disclosure, and update processes)

- Full standards test dossier

- If EU MDR applies: The technical documentation set with clinical evaluation and PMCF plan

- If U.S. applies: The 510(k)/De Novo/PMA package with software, EMC/safety, and human-factors evidence, and any applicable ASCA test declarations

Process: The review confirms manufacturing and quality controls can repeatedly build the verified/validated design, with robust supplier and change controls. It checks regulatory deliverables are consistent and that cybersecurity and SBOM obligations are operationalized per updated FDA guidance and Section 524B. The team verifies the post-market plan links PMS signals to risk management updates and meets EU MDR PMCF commitments. Finally, it ensures all design reviews are conducted, documented, and approved per 21 CFR 820.30(e) and ISO 13485.

Outputs: A signed Design Transfer/Release record; submission packages complete and approved; a controlled Device Master Record and Device History Record plan; and a surveillance/PMCF and cybersecurity lifecycle plan ready for launch.

What’s uniquely important for medical electronics: Transfer locks the EMC and safety critical parameters into production: component selection lists with alternates validated, PCB fabrication notes that preserve creepage/clearance and stack-up, shielding and gasket materials, enclosure coatings, and cable harness pin-outs. Software/firmware signing keys are controlled; build pipelines are frozen with provenance capture; and SBOM generation is automated as part of release.

Putting It All Together: The Review System as a Living Backbone

A mature design review system is cumulative and traceable. FDA’s regulation expects formal, documented reviews “at appropriate stages,” but leaves it to you to tailor frequency and composition. ISO 13485 frames reviews as part of a broader design and development control system. When these reviews are tied explicitly to risk management (ISO 14971), software lifecycle discipline (IEC 62304), usability engineering (IEC 62366-1), and electro-safety/EMC (IEC 60601-1/-1-2), the outcome is a complete evidence chain that withstands scrutiny and supports safe deployment.

Below is a concise view of what each stage contributes to that chain.

|

Stage |

Primary purpose |

Representative evidence |

|---|---|---|

|

Concept & Feasibility |

Confirm viable intended use, early risks, and standard/regulatory path |

D&D Plan, standards matrix, initial risk plan, system concept |

|

Design Input |

Freeze complete, testable requirements tied to needs and risks |

Approved input spec with traceability; cybersecurity/SPDF & SBOM requirements |

|

Architecture & Detailed Design |

Prove design outputs can meet inputs safely, securely, and accessibly |

Schematics, stack-ups, software architecture, usability/UI specs, threat model |

|

Verification Readiness |

Validate that test plans cover standards and risks comprehensively |

V&V master plan; EMC/safety/software/usability protocols with acceptance criteria |

|

Verification (results) |

Demonstrate outputs meet inputs under stress and single faults |

Test reports, requirements matrix, updated risk file, corrective actions |

|

Validation & Clinical Evidence |

Show the device meets user needs and benefit-risk is favourable |

Summative HF report, validation data, labelling/IFU, clinical evaluation & PMCF plan |

|

Transfer & Release |

Freeze design into production and submissions with lifecycle plans |

DDF/DHF, DMR, supplier controls, submission package, cybersecurity maintenance |

Conclusion

A successful medical device design review system is more than a set of meetings. It is the living backbone of your quality, safety, and compliance story. For medical electronics, the stakes are higher because risk is distributed across boards, bitstreams, binaries, and behaviour.

By structuring reviews into seven deliberate stages: Concept & Feasibility, Design Input, Architecture & Detailed Design, Verification Readiness, Verification (results), Validation & Clinical Evidence, and Transfer & Release. You create a disciplined cadence that connects user needs to clinical benefits through evidence.

The system anchors itself in FDA’s design control rule and ISO 13485, breathes through ISO 14971 risk management, and speaks the languages of IEC 60601-1/-1-2, IEC 62304, and IEC 62366-1. When cybersecurity and SBOM expectations are integrated from inputs to post-market maintenance, you not only meet regulator expectations but also make devices that are resilient in the real world. That is what “successful” looks like: safe, effective medical electronics that earn trust by design, by review, and by results.

Back

Back