Energy Harvesting Sensors for Medical Devices and Remote Sensors

Energy harvesting sources from the environment is a technique that uses natural or man-made energy sources and is now an increasingly popular technique for powering electrical devices. Solar-powered lights and pumps for decorative ponds are cheap, plentiful, and commonplace. Widespread exploitable energy sources include solar energy, natural geothermal and solar heating, man-made heating, and vibrational energy as a by-product of machinery, natural or artificial movement of gases or fluids, and man-made electromagnetic fields from wi-fi, radio, and television broadcasting.

A wide range of integrated circuits now harness various energy sources, each with distinct advantages. Geothermal heating offers a reliable, year-round supply but is limited to specific geographic regions, making it less practical for most electronics applications. Solar power, while widely available, is restricted to daylight hours and varies with the seasons and weather, making it less consistent.

Despite fluctuations, energy availability is often predictable over time. Engines powered by petrochemicals provide consistent thermal and vibrational energy during operation which can be harvested as a byproduct. But both diminish rapidly once the engine stops and the thermal source quickly decays. Choosing the right energy source depends on your device’s energy needs, operating conditions, and environment.

Common Energy Sources

Fluid flow is one of the oldest forms of energy harvesting sources, the flow of fluids has long been captured using windmills powered by the wind and waterwheels powered by streams and rivers. Turbines can be used to capture energy from the flow of any available gas or liquid, from hydroelectric power stations down to medical implants powered by blood flow.

Photovoltaic technology is now one of the most widespread technologies for harvesting solar energy, used in everything from small self-powered electrical devices to roof-top panels that supplement domestic and commercial energy usage and now reasonably common wide-area solar farms provide renewable energy as part of national power generation strategy. Typical implementations use amorphous silicon or dye-sensitized solar cells to generate electricity directly from solar energy. The power generated is proportional to the ambient lighting levels. However, the nature of sunlight in terms of brightness and frequency range means that it can typically be converted into greater energy levels than comparable artificial lighting.

Mechanical and Thermal Energy Harvesting Methods

The piezoelectric effect is the conversion of mechanical movement into electrical energy using crystals. Though it can harness any form of movement with continuous strain, the energy produced is minimal, making it suitable only for low-power devices like exercise monitors or sensors on rotating machinery. However, the piezoelectric effect degrades over time, limiting the lifespan of such devices.

The triboelectric effect, commonly observed as static electricity, is caused by pulling apart different materials to create an electric charge, an effect that can be maximized by rubbing two such materials together to create a continuous cycle of contact and separation. However, the effects of friction and the inevitable wear that will occur in the two triboelectric layers will significantly limit the device’s useful lifetime.

Thermoelectric generation is the conversion of a thermal gradient found at the junction of two dissimilar conductors into electrical energy, known as a thermocouple. A thermoelectric generator can be created from a series of semiconductor PN junctions linked together in a relatively compact component. However, the relative inefficiency of the process and the low currents generated to limit the applications for this technology. It is most commonly utilized in wearable medical health monitoring devices where body heat provides a dependable energy source.

The pyroelectric effect is the conversion of temperature change into electrical energy. While more efficient than thermoelectric harvesting, a continuous change of temperature is required to generate meaningful energy levels. The application of this technology is currently minimal.

Electrostatic or capacitive harvesting converts mechanical energy from vibrations acting on a capacitive device to change its capacitance into electricity energy. This is achieved by having one fixed plate and a second moveable plate that the external vibrations operate on. However, the capacitive device must have a significant potential difference applied before the vibrational energy can be harvested. This pre-charging of the capacitor will require an additional energy source.

Magnetic induction harvesting converts mechanical energy from movements or vibrations acting on a magnetic material to change the magnetic field into electrical energy. Most commonly used in generators and alternators to convert rotational energy from a mechanical engine or a fluid flow, on a smaller scale, vibrations acting on flexible magnetic materials can be used to generate small levels of electrical energy in a solid-state device.

Electromagnetic radiation can be collected using an antenna optimized for a particular frequency band or for a broad range of frequencies. Due to the relatively small energy levels available, radiation can be harvested from ambient wi-fi, radio, and television signals or from electromagnetic radiation directed explicitly to the collector for harvesting.

The biological process of using enzymes to break sugars down into constituent water and carbon dioxide to release energy offers potential applications in medical implants powered by harvesting blood sugar. However, it has limitations in terms of requiring access to a supply of suitable enzymes to sustain conversion.

Why Harvest Energy?

The advantage of energy harvesting PCB is the ability to place remotely located devices quickly and cheaply without needing to provide power over wires or use replaceable batteries. Energy stores in the form of batteries and capacitors can manage energy sources that are not available when the device is required to operate.

Energy harvesting is especially useful for remote sensing devices, such as energy harvesting sensors in medical equipment, which require only small amounts of energy to operate. These devices are often used in locations where providing an external power source is difficult.

Key benefits include:

- Continuous monitoring of mechanical systems to track status and predict faults.

- Reduction in maintenance costs by replacing scheduled checks with preemptive actions based on real-time performance data.

- Harvesting energy from available sources such as heat, movement, vibrations, and electromagnetic fields.

Health monitoring systems are a prime example of this application, making them ideal for industries looking to improve efficiency and reduce downtime.

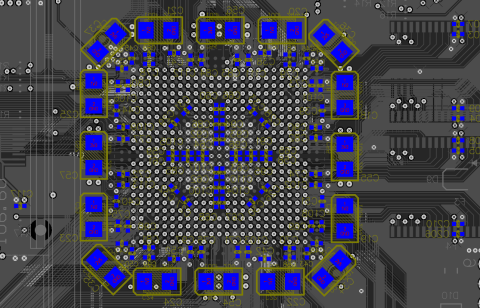

A typical remote sensor requires a sensing function, a data processing function, a wireless communications capability, and a power supply. The development of efficient integrated solutions for sensing, processing, and communications has facilitated replacing traditional battery-based power supplies with energy harvesting PCB. The availability of energy harvesting devices as the integrated circuit has simplified their incorporation into compact and rugged devices that can be deployed almost anywhere.

What’s the Best Source?

When looking to identify the best energy source to harvest from machinery, the search starts with internal and external sources. Internal sources, typically come in the form of heat or motion.

Heat can be generated from several sources:

- Inefficient components: These generate excess heat due to operational losses.

- Friction: Occurs when moving surfaces are in contact, producing heat.

- Exothermic reactions: Heat is a by-product of processes like chemical manufacturing or fuel ignition, such as in engines or furnaces.

Fuel-powered engines, for example, are often less than 50% efficient, creating significant heat that can be harnessed.

Motion can come from:

- Rotating machinery: Common in industrial settings.

- Vibrations: Caused by machinery in motion.

- Fluid movement: Generated by pipelines or environmental factors, including the movement of gas or liquid.

By understanding and utilizing these energy sources, efficiency can be greatly improved in various applications.

External sources, typically come in the form of light, heat, electromagnetic radiation, or motion. Light can be collected from sunlight or from any artificial lighting present. Heat can be collected from the indirect effect of sunlight heating a surface or from geothermal activity. Electromagnetic radiation can be collected from any ambient electromagnetic energy in the environment, found in high densities in the majority of urban areas and in lower levels where radio or television signals are broadcast. Motion can come from any naturally occurring movements of fluids such as wind or flowing water.

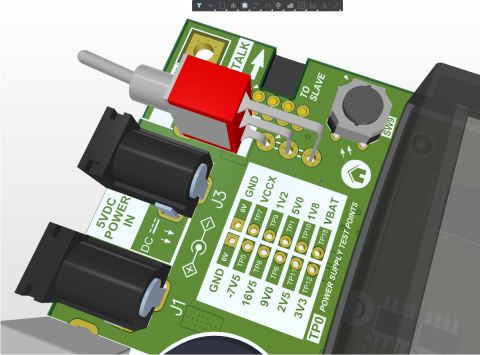

Implementing and Executing Devices for Energy Harvesting

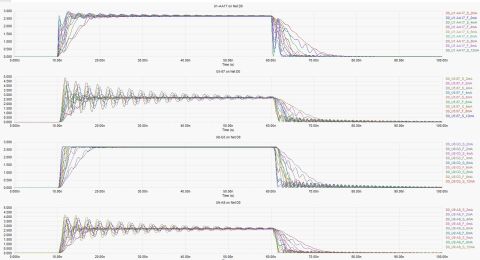

A range of off-the-shelf integrated circuits is now available that incorporate energy harvesting functions with power supply circuitry that can be dropped into a design in place of the usual power supply logic. A typical chip includes a cold-start circuit for initial power-up, an ultra-low-power boost converter to take the voltage generated by the energy harvesting components, a suitable voltage for the energy store, and a low-dropout regulator to provide usable power supply to the devices for energy harvesting PCB being powered. Integrated functions include energy storage management for fast charging, low power warnings, and selectable output voltage. Commonly available integrated circuits from the usual chip suppliers include:

- Solar-powered power management units with buck converters, buck-boost converters, and low-dropout regulators

- Thermoelectric-driven power management units with boost converters, buck-boost converters, and low-dropout regulators

- Magnetic-driven power management units with buck converters and buck-boost converters

- Piezoelectric-driven power management units with buck converters and buck-boost converters

Hybrid energy harvesting integrated circuits are also available where a single energy source will not meet the circuit design requirements. For example, combining different semiconductor materials into a single package can bring together photovoltaic cells and a thermoelectric generator in one chip. Similarly, organic materials are available that can be used to generate electrical charges for both photovoltaic and thermoelectric effects.

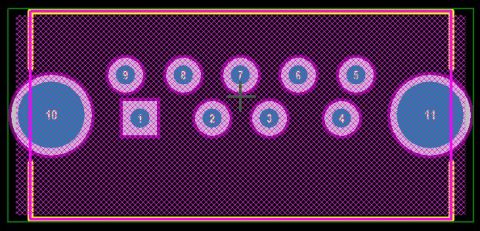

When implementing an integrated energy harvesting chip, additional components in the form of energy collection and storage components will be necessary. The collection element will typically be photoelectric cells, a radio frequency receiving antenna, or a thermocouple. The storage element will typically be a lithium-ion battery or a super-capacitor. It is also common to need to add external capacitors, inductors, and resistors in accordance with the datasheet. A typical chip will require less than ten passive discrete components in addition to the collection and storage elements.

Conclusion

The availability of integrated circuits that have energy harvesting functionality built-in makes the adoption of this power source straightforward when designing remote sensing devices with a ready source of energy available to be tapped into. Eliminating the need for batteries or a wired power supply can offer significant advantages over the long run in terms of through-life costs and potentially simplify the device’s design by removing the need for a battery compartment or a power socket.

Where availability of the energy source cannot be guaranteed, or in the case of sunlight where it is only available for set periods, an energy store will be required. The harvested energy provided to the store over a set period obviously must equal or exceed the energy taken from the store by the device over that period.

The main design question then becomes, which is the best source of energy to harvest, and of course, this doesn’t have to be a single source. Tapping into a couple of different energy sources may be preferable if no single source provides a dependable energy supply. It all depends on the operating environment, the operational requirements, and any budgetary constraints.

Talk to an Altium expert today to learn more or join one of our On-Demand Webinars for expert advice.

Back

Back