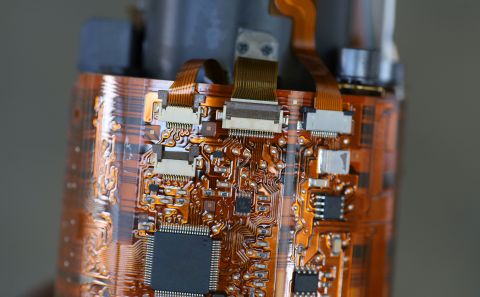

Fabrication Notes For Rigid-Flex PCBs

What is the number one thing that can be done to ensure first pass success on your flex or rigid flex design? If the first word that comes to mind is COMMUNICATION I couldn’t agree more. Although the “basics” of flexible circuit design are not all that different than a rigid printed circuit board, the devil is in the details as they say. There are a number of subtle differences that will help ensure your design performs as needed: Routing traces perpendicular to the bend area, material selection, teardrops or anchoring spurs, stiffeners, to name a few. But fabricators all agree, the number one thing you can do to stack the deck for the best possible first pass yield and performance with a new flex or rigid flex design is to communicate openly and often with your fabricator during the design process. They have built hundreds or thousands of flex designs over time and happily offer the wisdom gained.

A direct telephone call or even email communication during the design process is well worth the effort. The next step in communication is a clear and specific fabrication drawing. This ensures accurate communication between the designer and vendor and significantly increases the chances for first pass success.

Fabricators often complain of errors in the fabrication drawing, some citing errors in up to 75% of the documentation packages they receive. At best, this results in time wasted during the tooling process, but at worst this could cause failure during installation and performance.

Key Items to Include in a Rigid-Flex PCB Fabrication Drawing

IPC Class Specification

IPC standards define three classes of product. Understanding the requirements for manufacturing and inspection is critical and should be clearly stated in the fab drawing.

- Class 1 – Consumer products and products for non-critical applications where cost is normally the primary driver.

- Class 2 – Higher-order products in terms of quality and reliability expectations, including telecommunications, computers and general industrial.

- Class 3 – High-reliability applications including military, aerospace, automotive and medical products.

Manufacturing Tolerances

Fabricators need to understand what dimensions are critical and to what tolerance and PCG designers need to understand that certain tolerances will be different than when working with rigid printed circuit boards. Flex materials process differently than rigid materials.

Cover Layer Requirements Not Properly Called out of Defined

Coverlay or cover coat serves as a flexible solder mask protecting the circuitry and defining pad openings. It is crucial to communicate the dielectric thickness and adhesive thickness required. This may vary depending on end application, number of flexing cycles that will be required and how this contributes to overall thickness. This is a good topic to discuss with your fabricator when reviewing materials and material availability.

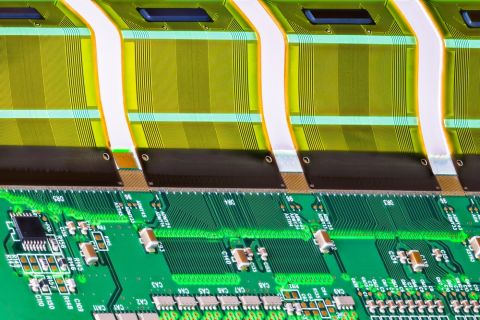

Separation Distance Between Flex Cores

When there are two or more flex cores, it is critical to specify the distance between those layers. These cores may be “bonded” or “unbonded” depending on performance requirements. When layers are bonded, it is also important to pay close attention to the overall thickness as those are built up. This can have a significant effect on flexibility. If using unbonded layers to increase the flexibility, it is critical that this is clearly communicated to the fabricator.

Example of bonded and unbonded layers provided by American Standard Circuits

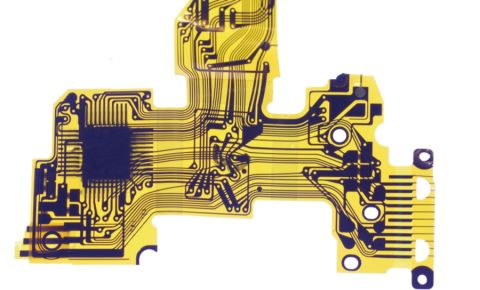

Unbonded flex layers provided by American Standard Circuits

Bend Radius and Flexing Requirements

The ability to flex and bend is one of the prominent benefits of using flexible materials. Care needs to be given to how the part will be flexing in end use. If the part will be bent once and remain stationary or if it will dynamically flexing for thousands of cycles, will each require a different level of analysis. Clearly communicate how the product will be bend, flex and fold and specifically ask your fabricator to review the artwork and materials. This is a critical area to involve your fabricator and lean on their experience. The commonly accepted guidelines for flexing are:

- For a single metal layer, the minimum bend radius should be on the order of 3-6 times the thickness of the circuit.

- For two metal layers, the minimum should be 7-10 times the thickness of the circuit.

- For multilayer flex, the minimum bend radius should be 15-20 times the thickness or more. If the multilayer sections are unbonded in the bend area, this rule might be relaxed.

- For dynamic flexing applications where high flex cycle life is required, again the design should be limited to a single metal layer and the bend radius made as large as possible (20-40 times thickness or more).

This is a short list of some of the most critical areas and a thought starter for review. I have referenced a few images from American Standard Circuits in this blog and highly recommend their free eBook discussing how to put together the best data package for flex and rigid flex. This eBook will provide more specific information and is a fantastic resource. It can be downloaded here.

Whether you need to build reliable power electronics or advanced digital systems, use the complete set of PCB design features and world-class CAD tools in Altium Designer®. To implement collaboration in today’s cross-disciplinary environment, innovative companies are using the Altium 365™ platform to easily share design data and put projects into manufacturing.

We have only scratched the surface of what’s possible with Altium Designer on Altium 365. Start your free trial of Altium Designer + Altium 365 today.