Power Integrity Measurements for Your Prototype Board

We often write about signal integrity and power integrity around here, but there is one area where we sometimes fall short: test and measurement. Both aspects of building a new device are critical for ensuring your board will work as intended and meets stringent performance requirements. With advanced systems, the level of testing and measurements required to qualify a prototype for full-scale production spans far beyond using a multimeter.

Power integrity measurements are extremely important as more systems run at lower voltages with smaller noise margins. Power integrity problems in your board can be the source of signal integrity problems, and the two areas of qualification shouldn’t be treated in isolation. Let’s take a look at some standard power integrity measurements required for digital, high frequency analog, and mixed signal systems.

Power Integrity Problems and Measurements

The entire point of having a power supply on your board is to ensure your components receive a stable voltage/current. In other words, you need to make sure that the 5 V provided by your power supply is still 5 V by the time it reaches your downstream components. IR drop is an obvious culprit of DC voltage drop, but there are other problems that can arise when we consider the behavior of real components connected to a power rail.

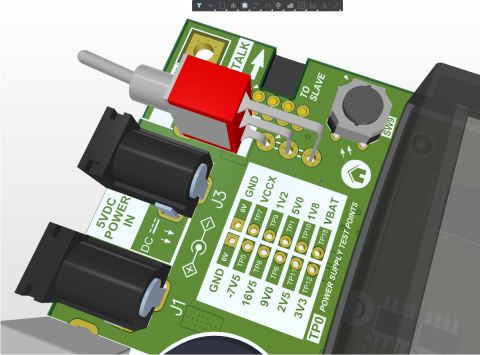

This is simple enough to simulate with a PDN analysis tool, but it is next to impossible to measure in a board with power and ground planes unless you install numerous test points that can connect to probes. If you are in the mood to test this, you essentially need to produce a test coupon that matches your stackup and includes test points for power/ground connections and some resistors. This is usually less important in high performance systems that run at high speed, high frequencies, or both.

Ringing on a power rail is much more important in these high performance systems. When an IC switches, it draws a burst of current from the power supply, which induces a transient oscillation in the PDN. Designing a PDN to critically damp this oscillation is quite difficult without tools for extracting parasitics and subsequent parameter optimization, and using a series resistor to provide damping (as is done with series over-termination in transmission lines) is out of the question as it increases the PDN impedance. Therefore, the standard approach is to make the PDN impedance as small as possible within the relevant bandwidth. This minimizes the voltage fluctuation on the PDN for a given transient current draw.

This should also illustrate the importance of decoupling, both with the right stackup design and decoupling capacitors. Decoupling capacitors have been given a rather unfortunate name as they don’t decouple anything (within the parlance of filtration). Your decoupling network needs to supply enough charge in a sufficiently short enough amount of time such that all the charge is drawn from the decoupling capacitor rather than the power supply. Transient ripple in the PDN can produce ~1 ps/mV or more of random jitter in the output from a digital IC. It is not uncommon to see clock jitter reach hundreds of ps, which creates problems in any channel running at high data rates.

If we think about these points, we see the five primary quantities that need to be measured in your PDN:

- The magnitude of the voltage ripple when critical components switch

- The PDN impedance spectrum

- Jitter produced due to ringing

- Variance in your clock period

- DC stability

Interpreting Power Integrity Measurements

Transient Response

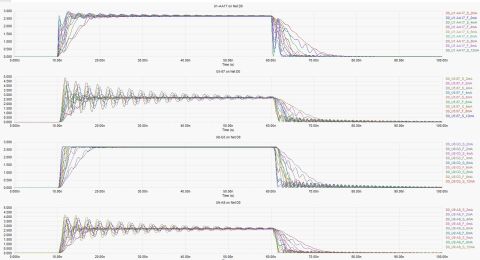

Let’s look at an example so you know what to expect when investigating point #1 above. Eric Bogatin, Teledyne LeCroy's resident signal integrity evangelist, has shown some very nice graphs in an earlier presentation, which nicely show the relationship between switching action and power plane voltage in the time domain. I'll show these as they are some of the clearest examples revealing the forced and transient power rail voltage on the PDN. I've linked to his original presentation in the captions below. You can also find these and other useful figures in Bogatin & Smith's textbook, Principles of Power Integrity for PDN Design--Simplified: Robust and Cost Effective Design for High Speed Digital Products.

The image below shows an example oscilloscope measurement of the transient voltage response on a PDN with an oscilloscope.

Once the test clock signal turns on, we see a repetitive transient response corresponding to the rising/falling edges from the clock pulses. This is superimposed over a lower frequency transient response. This lower frequency transient response is easily seen once the test signal switches off. If downstream circuits were running at 1.8 V with 2% tolerance, this PDN would fail qualification.

Impedance Spectrum Measurements

The impedance spectrum of the PDN can be determined on a test coupon with an impedance analyzer or a vector network analyzer that can run in impedance mode. If you do use a vector network analyzer, make sure that you de-embed the S-parameters for your connectors (usually BNC connectors for high-quality equipment) when performing the measurement. This measurement helps explain the transient behavior on your PDN and can help you determine how the stackup, decoupling network, or both need to change to reduce power bus ringing.

Jitter/Phase Noise Measurements

This is most easily determined from an eye diagram using the output from a downstream component. This is a standard measurement for I/O channels and will require installing some test structures for signal integrity on your board.

Clock Frequency Variation

Synthesized clocks (e.g., voltage-to-frequency converters, VCOs/NCOs, etc.) that are not locked to a highly stable reference clock (e.g., with a PLL) also experience some variation in the output frequency in addition to timing jitter. This also arises from the ripple in your PDN. An example for a 500 MHz clock is shown below. Here, we see that the variance in the clock period exceeds 10% in the presence of ~250 mV peak-to-peak ringing.

DC Stability

Measuring DC stability requires removing any blocking capacitor on the input of your oscilloscope and applying some voltage offset, bringing the DC signal into the midrange of your scope output. This allows you to see the influence of any low frequency content on the output from your power supply. You can also zero in on any hidden low frequency content by applying an FFT to your time-domain measurements.

The key to gathering all of these measurements is using an oscilloscope with sufficiently large bandwidth, high resolution, adjustable offset, and low impedance probes with low attenuation ratio. There are plenty of options on the market, but be sure to check these specifications with your scope manufacturer.

The pre-layout and post-layout simulation tools in Altium Designer® can give you a look into potential signal and power integrity problems in your board before your produce a prototype, giving you some hint of where potential problems may lie. You’ll also have access to a complete set of routing, manufacturing planning, and data management features in a single platform.

Now you can download a free trial of Altium Designer and learn more about the industry’s best layout, simulation, and production planning tools. Talk to an Altium expert today to learn more.