Does Just-in-Case Supply Chain Still Apply?

It’s widely known that Toyota’s ‘Just-in-Time’ (JIT) production strategy is one of the leanest and most effective methods of running a production line and supplying products to regular customers. However, the years of disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic that swept across nations, closing down all non-vital services in its wake, may have highlighted a vital flaw in this strategy from the perspective of supply chain risk management.

Now that organizations are aware of the impacts that one major global tragedy can have on the world—not to mention combining it with a short-haul disruption like that of the Suez Canal—this could potentially rebuild the case for a ‘Just-in-Case’ (JIC) approach. While this method of managing inventories has historically proven effective, do companies need to inject funds into stock just to ensure protection against potential barriers in the supply chain process?

JIC Versus JIT Supply Chain

Before exploring how the Just-in-Case supply chain can still apply in the modern business landscape, particularly in the electronics sector, it’s important to understand the nuances of each strategy and, ironically, the potential risks they incur.

The ‘Just-in-Time’ Strategy

A strategy ideated by Taiichi Ohno (father of the Toyota Production System) for application in the car maker’s manufacturing plants, JIT is a method of producing products or components with minimal wait times between steps in the process. In this process, Toyota preempts the next order and begins production to be ready for the next consignment to be released when customers reach their lowest point.

This is a great philosophy to adopt in manufacturing and has been praised for ingenuity as well as its reduction of costs, improved management of time, and limitations of warehousing space. In an ideal scenario, operating on a JIT basis allows the supply chain to run as continuously from end to end.

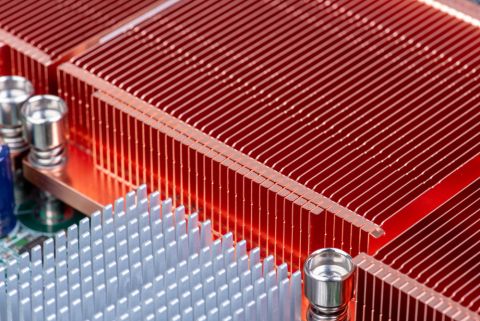

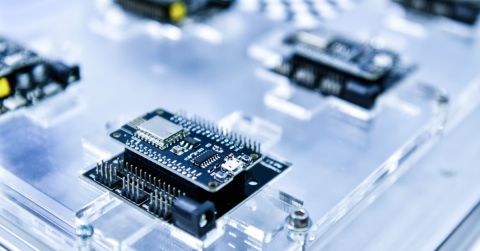

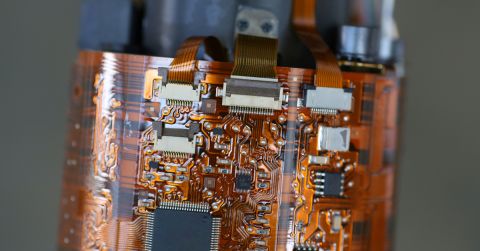

While JIT may begin to look more attractive in terms of cost and seamless production, this too has its own risk. Considering the nature of supply chain disruption, the efficiency of this strategy sacrifices resilience. If an unexpected event comes around the corner—take the Suez Canal incident as an example—JIT, which relies on a constant flow of parts, becomes somewhat problematic. If a printed circuit board (PCB) component supplier holds low or no inventory, then a major logistical nightmare such as this will inevitably halt its order fulfillment. Moreover, with zero inventory, disruption in the supply chain will lead to even more significant setbacks when building up to full production capacity.

It’s important to commend the team at Toyota for creating such an ingenious strategy for minimizing sunk costs. However, if an organization considers adopting such a philosophy, it should figure out a way to find a balance between lean manufacturing and supply chain resilience.

The ‘Just-in-Case’ Strategy

The very essence of JIC is what JIT sets out to avoid, but this doesn’t necessarily make one superior. Understanding the expenditure of JIC will determine whether it is more beneficial to hold inventories in case of external, unforeseen impacts on the business.

Ultimately, JIC can be labeled as the more traditional approach to supply chain management, carrying higher investment, requiring a warehouse for inventories, and its own set of potential risks. Looking closer to home presents its own form of risk—a warehouse fire would be enough to extinguish a large inventory (the NFPA estimated an average of 1,450 structure fires per year in the US) or natural disasters and unusual weather fronts, perhaps caused by ongoing pollution, might cause damage to precious stock.

Excluding such events, further costs are involved in keeping more inventory. This includes insurance—to address the aforementioned problems—as well as staffing, management, and rental of excess warehousing.

Create and Maintain End-to-End Visibility

To understand the significance of JIC, we must look beyond it and assess the nuances of JIT. The key to unlocking the full potential of JIT is visibility. Adopting risk mitigation as a strategy will likely result in conversations between buyer and supplier about end-to-end visibility and how both organizations can keep tabs on the process.

Collaborate with Suppliers

This can be a manual process for organizations that require bespoke PCB parts or generate higher order quantities, resulting in a much closer relationship with manufacturers. In this case, visibility may be subject to the supplier and their ability to provide data on lead times for components.

Diversify the Supply Chain

Leveraging Octopart, companies can achieve greater visibility and gain access to real-time updates and collaboration with suppliers. The market-leading electronic parts search engine holds the key to data on more than 40 million parts and gives the user a power platform to create a bill of materials (BOM) digitally. The Octopart platform is the gateway to information that will determine the most suitable suppliers for the business and can be integrated with the Altium Designer's ActiveBOM®—a unified solution for sharing design and parts requirements with internal stakeholders and manufacturers.

A strategic approach to managing the supply chain without taking inventories, using Octopart, provides visibility over a range of suppliers that could bolster any shortfalls in component supplies.

Environmental Awareness

There’s an aspect of sustainability to the JIT versus JIC debate. The inevitable spotlight on supply chains makes a case for waste management—or limiting the potential for waste. The global figure for electronic component waste is expected to increase to 74.7 million tonnes by 2030. It is easy to foresee how JIT can eliminate any potential waste management concerns, particularly among businesses that swap out components regularly for new electronic devices. Marrying a leaner production process with a clearer view of when more stock is required leaves minimal products in limbo between supplier and customer. Likewise, in the event of a product update or component upgrade, limited inventory is the most sustainable approach. When operating based on a JIT strategy, components are ordered for specific consignments, reducing the likelihood of waste.

Visibility is Key: Monitor the Supply Chain

Operating a JIT model requires the necessary visibility from suppliers in order to pull it off successfully. With that said, there is also the added benefit of prediction in terms of lead times, costs, and production scheduling.

Monitoring should begin at the purchasing stage—understanding whether the supplier has a stock of the required components—and flow through logistics to the shop floor and then assembly. Further visibility can be gained by understanding the lead times required by the customer.

Reduced Inventory Buffer: JIT systems operate with minimal safety, meaning they rely on the timely delivery of materials as they are needed. This reduces the cost of holding inventory.

Immediate Action: Good visibility can identify disruptions before they impact the business. Corrective action can be taken proactively to avoid extra costs. Room is given to find alternative suppliers or adjust production schedules.

Transparent Supplier Relationship: When suppliers and customers have end-to-end visibility, they can work more collaboratively to uncover delays or potential weaknesses in the supply chain. Alternatively, all parties can be involved in creating more efficiency.

Better Customer Service: Better visibility means a closer customer relationship. This can serve the business when disruptions ensue as customers understand production barriers.

Compliance and Reporting: The risk factor is inevitable, but when environmental disclosure comes into play, this can prevent progress in other business areas. Keeping an eye on the supply chain is a key sustainability practice.

Closing the JIT vs JIC debate

While there’s no concrete answer to the JIT versus JIC debate, having looked at the pros and cons of both strategies, it’s clear that there are aspects of each system that can be beneficial in both procurement and production. The JIT approach champions a much leaner and cost-effective approach whereby processes are streamlined and coupled with visibility. On the other hand, the JIC strategy shows its relevance when discussing supply chain risk and resilience, which is a conversation spurred on by recent global events.

Both strategies have necessary traits, so the ability to combine the best elements of each will allow manufacturers, suppliers, and customers to collaborate and future-proof their collective models. The common thread binding both approaches is the vital need for visibility in the supply chain: the ability to foresee, predict, and monitor supplier stock levels, the flow of materials, and information from end to end. This is an invaluable asset in today’s complex and interconnected world.